When Reviewing the Literature on the Effects of Medicaid on Health Care for the Poor

- Inquiry

- Open Access

- Published:

Effects of medicaid expansion on poverty disparities in wellness insurance coverage

International Journal for Equity in Health volume twenty, Commodity number:171 (2021) Cite this article

Abstract

Background

More than xxx states take either expanded Medicaid or are actively because expansion. The coverage gains from this policy are well documented, all the same, the impacts of its increasing coverage on poverty disparity are unclear at the national level.

Method

American Customs Survey (2012–2018) was used to examine the effects of Medicaid expansion on poverty disparity in insurance coverage for nonelderly adults in the United States. Differences-in-differences-in-differences design was used to analyze trends in uninsured rates by poverty levels: (1) < 138 %, (2) 138–400 % and (3) > 400 % federal poverty level (FPL).

Results

Compared with uninsured rates in 2012, uninsured rates in 2018 decreased past ten.75 %, 6.42 %, and i.eleven % for < 138 %, 138–400 %, and > 400 % FPL, respectively. From 2012 to 2018, > 400 % FPL group continuously had the lowest uninsured rate and < 138 % FPL group had the highest uninsured rate. Compared with ≥ 138 % FPL groups, there was a 2.54 % reduction in uninsured risk after Medicaid expansion among < 138 % FPL group in Medicaid expansion states versus command states. After eliminating the touch on of the ACA market commutation premium subsidy, three.18 % decrease was estimated.

Determination

Poverty disparity in uninsured rates improved with Medicaid expansion. However, < 138 % FPL population are still at a higher hazard for being uninsured.

Background

Large disparities in wellness insurance coverage, related to poverty, accept been a long-standing issue in the United States (United states) and a meaning concern amid policymakers and wellness care professionals. Co-ordinate to the Kaiser Family Foundation, as of 2019, individuals under 200 % FPL accounted for 30 % of the full US population [i]. This big proportion of low-income individuals signifies a need to investigate the disparities in poverty and insurance coverage, and more specifically, how healthcare reform has impacted coverage. Long-continuing disparities in coverage have consistently been a topic of discussion with multiple factors being considered as the cause for such differences. On one manus, studies accept identified insurance coverage as an important determinant for disparities in access to intendance [two, 3]. While, lack of health intendance access and insurance coverage could be major contributors to poverty disparities, as this decreases i'due south quality of life due to prolonged negative impacts of poverty and insurance status [iv, 5]. Policies that reduce disparities in health insurance coverage are likely to accept a broader issue on economic inequality [6]. Thus, it is imperative to examine the part of poverty and its association with access to care, to gain a deeper understanding of the disparities in the healthcare sector in order to better health equity.

Implemented in 2014, evidence of the Affordable Care Act (ACA) showed a significant decrease in the uninsured rate from 18 to 12 % [7]. The expansion of health insurance, both public and private, resulted in a internet increment of 16.9 million people gaining coverage between 2013 and 2015, assuasive millions of previously uninsured individuals to admission and utilize wellness care services [8]. The Medicaid expansion provision and the ACA market exchange subsidy contributed greatly to this sharp decline. As i of the major provisions of ACA, Medicaid expansion reduced health inequity by increasing access to health insurance coverage among low-income populations, who were at loftier hazard of being uninsured. Medicaid expansion expanded the enrollment eligibility criteria for Medicaid to 138 % Federal Poverty Level (FPL), [9] resulting in gains in coverage for millions of low-income adults in more than than 30 states [x]. Later the debate on whether to expand Medicaid vs. weighing alternative approaches (i.e. using individual insurance or increasing toll-sharing), more states have continued to expand Medicaid because information shows that low-income individuals who have historically experienced suboptimal access to care or gone without coverage, can benefit greatly from expansion [11,12,13].

Previous literature has examined the bear upon of Medicaid Expansion across various vulnerable populations (i.e. young mothers including pregnant women, veterans, people with disabilities, people with obesity, smokers, and immigrants) [14,15,16,17,xviii,19,xx], disease conditions (i.e. cancers, AIDS and mental diseases) [21,22,23,24,25,26,27,28,29,30], socio-demographics [31, 32], and healthcare services (i.eastward. inpatient, outpatient and preventive services) [33,34,35,36], after the policy was implemented. Additionally, state-level analyses accept been conducted to assess the impacts of expansion, as Kentucky and Indiana have been well discussed [37, 38].

Regarding the policy impact on insurance coverage rates and healthcare access, several researchers have examined this topic and concluded that the rate of persons insured increased due to Medicaid expansion in all cases. Huguet and colleagues examined the changes in uninsured visits across 412 primary care community wellness centers using electronic health records between 2012 and 2015 [39]. Blumberg et al. (2016) provided an overview of the characteristics of newly insured due to the ACA and those remaining uninsured in 2016 [40]. Other studies analyzed the insurance coverage gain of Medicaid expansion along with ACA by 2015 or 2016 [41,42,43,44,45]. Across each of these studies, researchers found that the charge per unit of persons insured increased due to Medicaid expansion in all cases.

Even so, these studies but restricted the policy impact to the offset- and 2d- year following Medicaid expansion in 2014 and did non distinguish Medicaid Expansion from other ACA provisions (i.e., market substitution subsidy, young adults remaining on parents' wellness insurance plans until they accomplish age 26, etc.). The ACA market place exchange subsidy eligibility is based on income, where individuals must earn at least 100 % FPL (above 138 % FPL in states that accept expanded Medicaid), but no more 400 % FPL. This premium subsidy can increase access to insurance for those between 100 and 400 % FPL. Therefore, it must be distinguished from the Medicaid expansion provision when analyzing the Medicaid expansion policy lonely. Additionally, as different states adopted Medicaid expansion at different times, the dynamic effects seen across adoption of the policy have not been clearly examined in previous research.

To address these gaps, this written report aimed to document changes in health insurance coverage for nonelderly United states of america adults, aged 26–64, from 2012 to 2018 and evaluate the effects of the dynamic adoption of Medicaid expansion on poverty disparities in wellness insurance coverage at the national level. With a longer post-policy period, our written report aimed to use causal inference to capture precise estimations of the sole furnishings of the Medicaid Expansion provision.

Conceptual Model

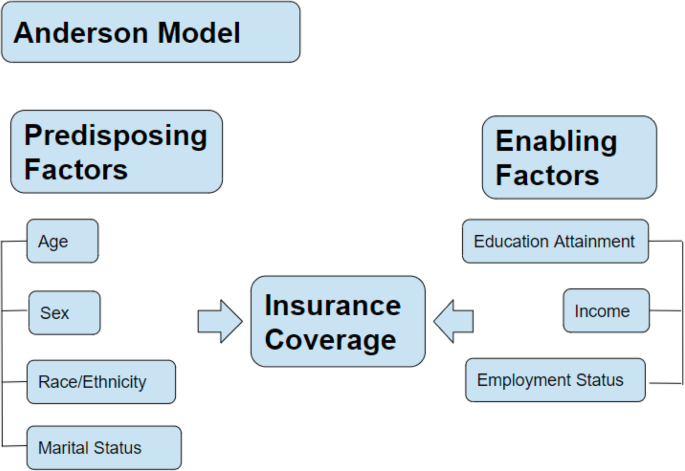

To address this study objective, the Andersen Behavioral Model for access to health care, derived from the original Anderson Healthcare Utilization Model, was adjusted for this study [46]. This model illustrates that in that location are certain factors that increment ane'south likelihood of using wellness care services and these are determined by 3 mechanisms of action: predisposing factors, enabling factors, and need. "Predisposing factors" are defined as demographic variables such as age, sex, race/ethnicity, marital status, education, employment, and poverty/income. The "enabling gene" in this study would be insurance coverage, and the "demand" is access to health care services (Fig. 1).

Conceptual Framework: Anderson Model

Methods

Data

This report used publicly available data that was waived from review by the Institutional Review Board at Tulane University. Data analysis was based on repeated cantankerous-sectional national population level data from the 2012–2018 7-year American Customs Survey (ACS) Public Employ Microdata Sample (PUMS) files. ACS is a very large survey, in terms of number of respondents who consummate the survey, making it possible to obtain estimations for narrowly defined subpopulations past FPL [47]. PUMS are a sample of actual responses from the ACS and include most population and housing characteristics. This information source, with the flexibility to set up customized tabulations, can be used for detailed research and analysis. In the PUMS, files have been de-identified to protect the confidentiality of all individuals and households. Farther, this survey includes information near socio-economical, demographics, and other characteristics. The PUMS file contains over 3.v million respondents each year with an average response rate of over 97 %. The differences in this cross-sectional survey were constant over fourth dimension, which makes the estimation of trends in insurance coverage comparable [48].

Analytic Strategy

This study employed differences-in-differences-in-differences (triple-D) design by comparison the result (health insurance coverage), before and later the intervention (implementation of Medicaid expansion) for the treatment group (individuals nether 138 % FPL) and control group. This quasi-experimental design has been widely used to guess the effects of a specific intervention or treatment past comparing the changes in outcomes over time betwixt a population that is enrolled in a policy/plan (i.e. the intervention grouping) and a population that is non (i.east. the command group) [49, 50]. The approach removes biases in post-policy period comparisons betwixt the handling and control group that could be the upshot from permanent differences between those groups, as well as biases from comparisons over time in the handling group that could be the result of trends due to other causes of the outcome.

In this study, we did non include data prior to 2012 and excluded individuals less than 26 years quondam, every bit a provision of the ACA enables young adults to remain on their parents' insurance plans until 26 years quondam. Without capturing effects of that provision, which take been well studied in previous research, our results excluded this potential confounding touch on [51,52,53]. Additionally, a 0 to one intensity was used to demonstrate the effect of the dynamic enrollment of adoption of the policy for each state in guild to generate more precise estimates.

The beginning regression was performed with the entire sample, with the treatment group being those nether 138 % FPL and the control group being those with FPL above 138 %. The second regression included those under 138 % FPL equally the treatment group and those in a higher place 400 % FPL as the control grouping. Those with an FPL range from 138 to 400 % were excluded in club to eliminate the ACA market exchange subsidy influence on the insurance coverage rate. The equation is as follows:

$$ \begin{array}{*{20}fifty} (ane) &{Uninsured}_{isy}=\beta_{0} + \beta_{ane}{Expanded}_{isy} + \beta_{2}\gamma_{sy} + \beta_{iii}\delta_{is} + {\beta}_{4}\eta_{iy}+ \beta_{5}{Poverty}_{isy} + \beta_{six}{Country}_{iy}+ \\ & \beta_{vii}{Yr}_{is} + {\beta_5X}_{isy} + \epsilon_{isy} \\ (two) & {Expanded}_{isy} = {Medicaid\_Expansion}_{sy}\ast{Poverty}_{isy}\end{array}$$

(one)

Variables and Measures

Uninsured isy was the study consequence. It was derived by the survey question "whether the individual has whatever insurance coverage" and was transformed into a dichotomous variable where 1 equaled no health insurance and 0 equaled having any insurance.

Expanded isy , variable of interest, was the interaction term that measured the individual level of Medicaid expansion status. This variable was calculated by Medicaid_Expansion sy times Poverty isy . In the first regression, the coefficient of this variable reflected the impact Medicaid expansion had on insurance coverage between persons below 138 % FPL (treatment group) and above 138 % FPL (control group) in yr \(i\)and country \(s\). In the 2d regression, the command group were the individuals above 400 % FPL.

Medicaid_Expansion sy was the Medicaid expansion policy indicator variable, defined as a varying intensity variable from 0 to 1. When a land expanded Medicaid, this variable equaled 1, otherwise, it equaled 0. For states that adopted the policy at the beginning of the year, fourth dimension before this sure year was the pre-policy period and from this year to 2018 was the post-policy period. Coverage under Medicaid expansion became effective January 1, 2014 in all states that adopted the policy except the following: Michigan (4/1/2014), New Hampshire (8/fifteen/2014), Pennsylvania (i/1/2015), Indiana (2/ane/2015), Alaska (9/i/2015), Montana (1/i/2016), Louisiana (7/1/2016) [54]. For the above states, the indicator variable was coded as the portion of the twelvemonth and so equaled to i in the following postal service-policy period. Specifically, the treatment for Michigan in 2014 was 275/365; the handling for New Hampshire in 2014 was 138/365; the treatment for Indiana in 2015 was 334/365; the handling for Alaska in 2015 was 122/365; and the treatment for Louisiana in 2016 was 184/365. Substantive Medicaid expansion policies prior to the state's official implementation date of Medicaid expansion were not considered in the written report. Still, the prior adoption of Medicaid expansions in some states (IN, ME, TN, and WI) were quite limited with capped or closed enrollment. In some states a mild form of Medicaid expansion was adopted prior to the enactment of the ACA for both parents and childless adults (DE, DC, MA, NY, VT), which turned out to be an equivalent of the ACA expansion.

Poverty isy , was divers as a chiselled variable using FPL threshold. FLP was calculated using poverty guidelines (one of the federal poverty measures) and the number of persons living in a household [55]. The poverty guidelines are updated each yr past the U.s. Department of Health and Human being Services, for use for administrative purposes (eastward.k., determining financial eligibility for federal Medicaid programs). In the first regression, 138 % FPL was used as the cutting-off point, where 1 was the population below 138 % FPL and 0 represented the population above 138 % FPL (command grouping). In the second regression, 1 represented those below 138 % FPL and 0 represented those in a higher place 400 % FPL (command group).

\({\gamma }_{sy}\) was the interaction term for year and land.\({\delta }_{is}\) was the interaction term for whether the individual was under 138 % FPL in a specific state. \({\eta }_{iy}\) was the interaction term for whether the private was under 138 % FPL in a specific twelvemonth (2012–2018).\({Country}_{iy}\) indicated the residence of land for the individuals in a given year. \({Year}_{is}\) represented the calendar year for the individuals in a state.

\({Ten}_{isy}\)was a series of individual demographic and socioeconomic covariates based on the Andersen model. Historic period, sex, race/ethnicity, marital status, pedagogy attainment, and employment status were adjusted in each model and these variables have been widely used in the literature to examine health care admission and utilization [4, 5, 56, 57]. Historic period was measured every bit a chiselled variable: 26–34, 35–44, 45–54 and 55–64. Sex was besides a categorical variable, where 1 was male person and 0 was female person. Survey participants were asked to self-study their race (White, Black/African American, American Indian/Alaska Native, Asian, Native Hawaiian/other Pacific islander, or multiple race) and ethnicity (Hispanic/Latino: yeah/no) separately. A 4-category race/ethnicity variable was coded as follows: participants reporting Hispanic/Latino ethnicity were considered Hispanic, regardless of race; all non-Hispanics were categorized as White, Blackness, or other races. Thus, Whites were coded as 0, Blacks, Hispanics, and Others were coded as 1, 2 and iii, respectively. Marital status was self-reported and categorized as married, widowed, divorced, and separated, and never married. For the model, we coded married as 0 and combined widowed, divorced, and separated into one group, and coded this group every bit (one) Self-identified pedagogy level was grouped past less than loftier school coded every bit 0, high school graduate, GED, or alternative coded equally i, and available's caste or higher coded as (2) Current employment status was categorized as unemployed coded equally 0, employed coded equally one, and non in the labor force coded equally 2.

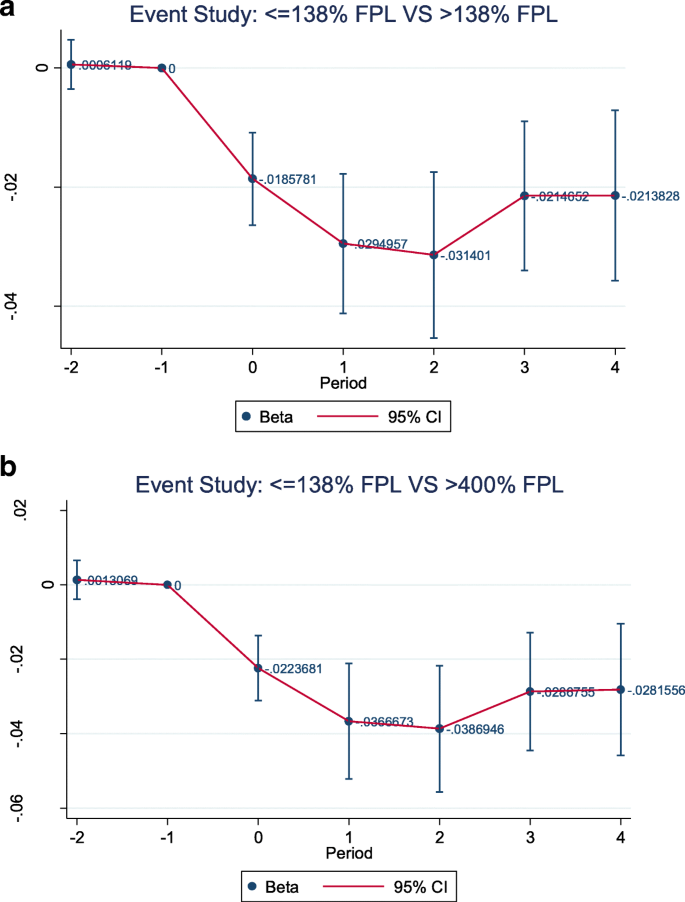

Robustness checks were performed to examination whether Medicaid expansion had an effect [58, 59]. To test this, we verified whether the control group (individuals with < 138 % FPL in non-expansion states) served equally a good comparison for the treatment grouping (individuals with < 138 % FPL in states that expanded Medicaid). Therefore, we tested if the trends in the two groups were parallel before the policy was implemented. This assumption was tested indirectly by employing an consequence study model that interacted the handling variables with the total set of fixed year effects. The regression took the course every bit Eq. 2 below. To satisfy the parallel trends assumption, no statistical significance on the first coefficient was expected, which suggested no change associated with Medicaid expansion betwixt the period at least 2 years and 1 year prior to expansion. Statistical significance in later years' coefficients indicated the expansion effected the treatment group with the given poverty level. In addition, nosotros too examined the association of Medicaid expansion with a placebo outcome unrelated to insurance status that would not be affected by the policy. The placebo outcome was fix as the probability of getting college education. The placebo outcome check was performed in the aforementioned format as Eq. 1.

$$ {Uninsured}_{isy}={\beta }_{0}+{\beta }_{i}{Pre2*Poverty}_{isy}+{\beta }_{3}{Same0*Poverty}_{isy}+{\beta }_{3}{Post1*Poverty}_{isy}+{\beta }_{4}{Post2*Poverty}_{isy}+{\beta }_{5}{\gamma }_{sy}+{\beta }_{6}{\delta }_{is}{+ \beta }_{7}{\eta }_{iy}+{\beta }_{8}{Poverty}_{isy}+{\beta }_{9}{State}_{iy}+{\beta }_{ten}{Year}_{is}+{\beta }_{eleven}X_{isy}+{\epsilon }_{isy} $$

(2)

Like to the master estimating equation (Eq. i), only the Expanded isy treatment variable was changed from the main model into a prepare of fourth dimension dummies for individuals given the yr and state (\(Pre2, Same0, Post1,Post2\), time \({Poverty}_{isy}\), respectively) in Eq. 2. The \(Pre2\) term was an indicator variable set as ane and represented at least 2 years before a country expanded Medicaid and 0 otherwise. The second \(Same0\)was 1 when in the year a land expanded Medicaid and 0 otherwise. Same algorithm followed for the \(Post1\) and \(Post2.\) The omitted category \(Pre1\) was the year immediately earlier expansion. Thus, the coefficients on each of these variables gave the alter for ii-year before expansion and 2-yr mail service expansion. Other variables in Eq. 2 represented the same state/yr stock-still furnishings and control vectors as Eq. ane. Standard errors were clustered at the state level to account for state-level differences and series autocorrelation. The seven-year data was a multi-year combination of the 1-year PUMS file with appropriate adjustments to the weights and inflation adjustment factors. The significance level for tests was set equally 0.05. The data was weighted by the ACS survey weight and analyses were performed using SAS 9.4 and Stata 12.0.

Results

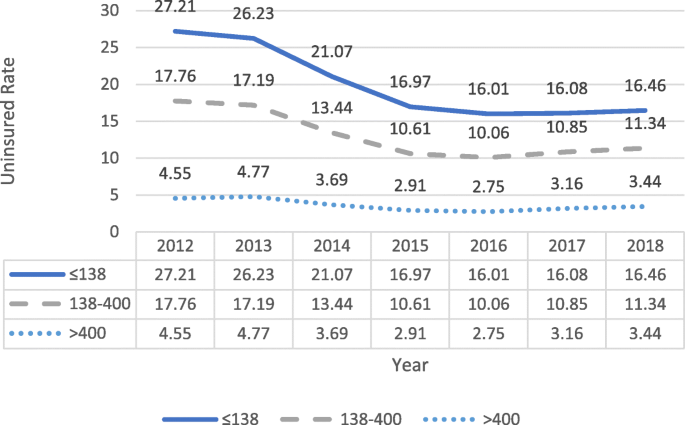

Figure 2 presents the trends in the uninsured rate from 2012 to 2018 by poverty level groups. The uninsured rates reduced significantly later on the market exchange subsidy and implementation of Medicaid expansion for all poverty levels. Specifically, compared with the uninsured rates in 2012, the uninsured rates in 2018 decreased by 10.75, 6.42, and i.eleven % points for individuals under 138 % FPL, between 138 and 400 % FPL, and in a higher place 400 % FPL, respectively. Although the uninsured rate decreased for all groups, those under 138 % FPL still had the highest uninsured rates.

Uninsured rate trends from 2012 to 2018 by poverty level

Table 1 presents the pre-policy period comparison on demographic and socioeconomic characteristics between states who adopted Medicaid expansion on January 1, 2014 with states who did not prefer the policy at that time. Both adopted and not-adopted states presented like age and gender distributions with more than than 50 % people being over 45 years onetime and about 51 % female person. Majority of the population were married and employed. White was the bulk race/ethnicity while Blackness made up eight % in adopted states and fourteen % in non-adopted states. Overall, Medicaid expansion states had a college education level (35 % received Bachelors' degree or higher). Expanded states also had a much higher mean FPL than states without expansion (423 % FPL vs. 329 % FPL, respectively). Chi-square tests for chiselled variables and two sample t-test for continuous variables were performed to explore the differences between adopted and non-adopted states by year 2014. All characteristics except gender showed statistically pregnant differences among adopted states and not-adopted states before Medicaid expansion took event.

Tabular array 2 displays the results of the two regressions based on the triple-D design, each with a basic linear model and multivariate linear probability model with controlled covariates. For the first basic regression, those nether 138 % FPL versus those higher up 138 % FPL, in that location was a two.44 % point decrease in uninsured hazard after expansion among those nether 138 % FPL in adopted states versus control states. Controlling for socio-demographic characteristics, in that location was a decrease of 2.54 % points in uninsured risk which almost doubled the uncontrolled model's reduction. For the 2d regression comparing those under 138 % FPL and higher up 400 % FPL, the unadjusted model showed a decrease of iii.09 % points in the uninsured probability while the adjusted model showed a decrease of 3.19 % points. Results also indicated individuals under 138 % FPL were notwithstanding 12.78 % points and 19.77 % points more likely of being uninsured nether expansion compared to those above 138 % FPL and above 400 % FPL, respectively. Further, equally age increased, the likelihood of existence insured as well increased. Among all race and ethnicities, compared with whites, Hispanics were the most unlikely to accept insurance.

Figure 3a and b present event study graphs that meet the parallel trends assumption in the pre-policy period between the adopted states and the control states. The graphs too showed that if Medicaid expansion had not occurred, changes in insurance coverage would accept not been correlated with pre-treatment uninsured rates. The placebo outcome robustness check reported insignificant results with p-values equal to 0.634 for regression ≤ 138 % FPL and > 138 % FPL, and 0.545 for regression ≤ 138 % FPL and > 400 % FPL, respectively. With both regressions' p-values greater than 0.05, placebo checks showed that Medicaid expansion did not have an affect on our effect, unrelated to the policy.

a Event Study - ≤138 % FPL VS > 138 % FPL. b Result Written report - ≤138 % FPL VS > 400 % FPL

Give-and-take

After a long mail-Medicaid expansion menses, our study examined the effects of the dynamic adoption of Medicaid expansion on poverty disparities in wellness insurance coverage at the national level. Findings from this study demonstrate that trends in the uninsured rate for each FPL group decreased from 2012 to 2018. Beyond all seven years, the "over 400 % FPL" group continuously had the everyman uninsured rate while the "under 138 % FPL" group had the highest uninsured rate. For all FPL groups, the uninsured rates were reduced significantly after implementation of Medicaid expansion. Through the triple-D design, both regressions showed a significant reduction in uninsured risk was due to Medicaid expansion.

This written report documented that a large increase in Medicaid eligibility was associated with a significant decrease in the uninsured charge per unit during the study menstruation. We also institute that the population with the largest coverage gains from expansion were those aged 55–64 years sometime, well-educated, and employed. For example, our results plant that individuals with bachelor's degree or higher were 14.24 % less likely to be uninsured compared with individuals who had less than a high schoolhouse educational activity. These findings may influence states' decisions with respect to Medicaid expansion.

Previous studies accept identified the benefits of Medicaid expansion on health insurance coverage amid individuals with low socioeconomic condition. Nonetheless, this written report further added to the literature with novel contributions. The overall results of this study extended the literature in several ways. Offset, this paper presented new evidence used a big national level survey and longer time frame to assess the association of expansion and insurance coverage. Many datasets such as the Behavioral Adventure Gene Surveillance Organisation, Gallup-Healthways Well-Being Index (daily national phone survey), and federal survey information, have been used to assess the socioeconomic disparities in health care access [43,44,45, 56]. Studies using these datasets found that health care access for people in lower socioeconomic strata had college improvement in states that expanded eligibility for Medicaid under the ACA than states that did not. Socioeconomic disparities in health intendance access narrowed significantly under the ACA. Rather than assessing the early stage of the starting time- and second- year of Medicaid expansion, our study reached similar conclusions using comparable study blueprint only in unrelated, population-based survey data. In addition, to report the clan between Medicaid expansion and insurance coverage among low-income populations, our written report demonstrated a more precise interpretation of this human relationship past using a varying intensity policy variable and eliminating the effect of parents' health insurance coverage for young adults under 26 years of age and the ACA premium subsidy. Sommers et al. plant that increasing insurance coverage increased health intendance utilizations by conducting a triple-D analysis of survey data from Nov 2013 through Dec 2015 on U.s.a. citizens ages 19 to 64 years former with incomes below 138 % FPL in Kentucky, Arkansas, and Texas [45]. Our findings were consistent with this country-level research and strengthened the conclusion at a national level that poverty disparities were narrowed by increases in insurance coverage.

Secondly, the triple-D estimates started with the average time changes for the population under 138 %FPL in the expanded states, and then netted out the alter in ways for the population under 138 %FPL in the control states and the alter in means for the population over 138 %FPL in the expanded states. This controlled for two types of potentially confounding trends: changes in insurance coverage for the population under 138 %FPL across states (that would have cypher to do with the policy) and changes in health condition of all people living in the expanded states (possibly due to other state policies that affect everyone's insurance status, or state-specific changes in the economy that affect everyone's insured rate). The triple-D blueprint immune us to estimate the coincidental bear upon of Medicaid expansion and contributed to an evidence-based policy decision-making process.

This study is non without its limitations. First, due to data availability, we were just able to estimate the effects upward until 2018. Therefore, some states, such equally Louisiana, had a very brusk post-policy period. Additionally, for states that adopted Medicaid expansion later on 2018, their effects were not seen. As future waves of data go available, information technology is worthwhile to revisit these estimates. Another limitation of this study is that detailed policy differences inside each state were non considered. Some states had different eligibility criteria for Medicaid prior to the adoption of expansion. In other words, the policy affect varied in the adopted states due to the earlier-adoption eligibility criteria. Further studies may examine these differences to get the unbiased policy effect. Lastly, ACS did not incorporate detailed health information such as disease atmospheric condition and healthcare utilization. Controlling for pre-atmospheric condition of individuals, could improve the precision of our estimates, and with specific healthcare utilization measurements, we could improve sympathize the straight impact of this policy on healthcare utilization.

Conclusions

In this written report, health insurance coverage improved substantially amidst populations with income less than 138 % FPL. Overall, Medicaid expansion has made impressive strides in reducing wellness inequity with increasing access to health insurance coverage among depression-income populations. Our findings are consistent with previous literature and reflect the accomplishment of Medicaid expansion's goal, making healthcare accessible for low-income populations. However, individuals under 138 % FPL are withal more likely to be uninsured.

Unlike other developed countries, the US does non have universal health insurance programs in which the regime plays a ascendant role. One major challenge of the US healthcare organization is providing equitable access to intendance. Disparities in health outcomes by income status are persistent and hard to reduce in the US. Therefore, the ACA and Medicaid expansion are critical to expand health insurance to improve overall quality of life for US citizens. Based on our findings, adequate access to health intendance services even so falls short and there is still a long way to become to attain healthcare equity. Healthcare professionals and policy makers should continue to abet for increased coverage for low-income populations. Reducing health inequity in health insurance coverage is achievable simply will crave better outreach to the remaining uninsured, specially amongst vulnerable groups with historically low and disproportionate uninsured rates.

Availability of information and materials

The American Customs Survey data is public data bachelor on the ACS official website.

Abbreviations

- ACA:

-

Affordable Intendance Act

- ACS:

-

American Community Survey

- FPL:

-

Federal Poverty Level

- PUMS:

-

Public Employ Microdata Sample files

- Triple-D pattern:

-

Differences-in-differences-in-differences design

- DC:

-

District of Columbia

- DE:

-

Delaware

- IN:

-

Indiana

- MA:

-

Massachusetts

- ME:

-

Maine

- NY:

-

New York

- TN:

-

Tennessee

- VT:

-

Vermont

- WI:

-

Wisconsin

References

-

Distribution of the Full Population past Federal Poverty Level (above and below 200% FPL) The Henry J. Kaiser Family unit Foundation. 2019. Retrieved Mar ten 2020, from: https://www.kff.org/other/state-indicator/population-upward-to-200-fpl/?currentTimeframe=0&sortModel=%7B%22colId%22:%22Location%22,%22sort%22:%22asc%22%7D

-

Hadley J. Sicker and poorer—the consequences of being uninsured: a review of the research on the relationship between health insurance, medical care employ, wellness, work, and income. Med Intendance Res Rev. 2003;threescore(2_suppl):3S–75S.

-

Schoen C, DesRoches C. Uninsured and unstably insured: the importance of continuous insurance coverage. Health Serv Res. 2000;35(1 Pt ii):187.

-

Satcher D, Fryer GE Jr, McCann J, Troutman A, Woolf SH, Rust G. What if we were equal? A comparison of the black-white mortality gap in 1960 and 2000. Wellness Aff (Millwood). 2005;24(2):459–64.

-

Zsembik BA, Fennell D. Indigenous variation in health and the determinants of health among Latinos. Soc Sci Med. 2005;61(1):53–63.

-

DeNavas-Walt C. Income, poverty, and health insurance coverage in the U.s.a. (2005): Diane Publishing; 2010.

-

Cohen RA, Martinez ME, Zammitti EP. Wellness insurance coverage: early on release of estimates from the National Health Interview Survey; 2015.

-

Carman KG, Eibner C, Paddock SM. Trends in health insurance enrollment, 2013-fifteen. Health Aff (Millwood). 2015;34(6):1044–8.

-

Rudowitz R, Musumeci M. The ACA and Medicaid expansion waivers: Kaiser Commission on Medicaid and the Uninsured; 2015.

-

Antonisse L, Garfield R, Rudowitz R, Artiga S. The effects of Medicaid expansion under the ACA: updated findings from a literature review.

-

Hayes SL, Riley P, Radley DC, McCarthy D. Closing the gap: past functioning of health insurance in reducing racial and indigenous disparities in access to care could be an indication of time to come results. New York: Commonwealth Fund; 2015.

-

Clemans-Cope L, Kenney GM, Buettgens Grand, Carroll C, Blavin F. The Affordable Intendance Act's coverage expansions will reduce differences in uninsurance rates by race and ethnicity. Health Aff (Millwood). 2012;31(5):920–thirty.

-

Sealy-Jefferson S, Vickers J, Elam A, Wilson MR. Racial and ethnic wellness disparities and the Affordable Care Human action: a condition update. J Racial Ethn Health Disparities. 2015;ii(4):583–viii.

-

Johnston EM, McMorrow South, Thomas TW, Kenney GM. ACA Medicaid expansion and insurance coverage among new mothers living in poverty. Pediatrics. 2020;145(5):e20193178. https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.2019-3178 Epub 2020 April 15. PMID: 32295817.

-

Clapp MA, James KE, Kaimal AJ, Sommers BD, Daw JR. Association of Medicaid expansion with coverage and access to care for pregnant women. Obstet Gynecol. 2019;134(5):1066–74. https://doi.org/x.1097/AOG.0000000000003501 PMID: 31599841.

-

O'Mahen PN, Petersen LA. Effects of state-level Medicaid expansion on veterans health administration dual enrollment and utilization: potential implications for time to come coverage expansions. Med Intendance. 2020;58(vi):526–33. https://doi.org/10.1097/MLR.0000000000001327 PMID: 32205790.

-

Stimpson JP, Kemmick Pintor J, McKenna RM, Park Southward, Wilson FA. Clan of Medicaid expansion with health insurance coverage among persons with a disability. JAMA Netw Open. 2019;two(7):e197136. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2019.7136 PMID: 31314115; PMCID: PMC6647921.

-

Rajbhandari-Thapa J, Zhang D, MacLeod KE, Thapa 1000. Impact of Medicaid expansion on insurance coverage rates among developed populations with depression income and by obesity status. Obesity (Silver Bound). 2020;28(seven):1219–23. https://doi.org/10.1002/oby.22793 Epub 2020 Apr 18. PMID: 32304356.

-

DiGiulio A, Haddix G, Bound Z, Babb S, Schecter A, Williams KS, et al. Land Medicaid expansion tobacco cessation coverage and number of developed smokers enrolled in expansion coverage - The states, 2016. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2016;65(48):1364–9. https://doi.org/10.15585/mmwr.mm6548a2 PMID: 27932786.

-

Stimpson JP, Wilson FA. Medicaid expansion improved health insurance coverage for immigrants, merely disparities persist. Health Aff (Millwood). 2018;37(10):1656–62. https://doi.org/10.1377/hlthaff.2018.0181 PMID: 30273021.

-

Wright BJ, Conlin AK, Allen HL, Tsui J, Carlson MJ, Li HF. What does Medicaid expansion mean for cancer screening and prevention? Results from a randomized trial on the impacts of acquiring Medicaid coverage. Cancer. 2016;122(5):791–7. https://doi.org/10.1002/cncr.29802 Epub 2015 Dec nine. PMID: 26650571; PMCID: PMC6193753.

-

Nikpay SS, Tebbs MG, Castellanos EH. Patient protection and Affordable Intendance Act Medicaid expansion and gains in health insurance coverage and access among cancer survivors. Cancer. 2018;124(12):2645–52. https://doi.org/10.1002/cncr.31288 Epub 2018 Apr 16. PMID: 29663343.

-

Toyoda Y, Oh EJ, Premaratne ID, Chiuzan C, Rohde CH. Affordable Intendance Act country-specific Medicaid expansion: touch on on health insurance coverage and breast Cancer screening rates. J Am Coll Surg. 2020:S1072-7515(xx)30213-i. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jamcollsurg.2020.01.031 Epub ahead of print. PMID: 32272206.

-

Weiner AB, January S, Jain-Affiche 1000, Ko Os, Desai AS, Kundu SD. Insurance coverage, stage at diagnosis, and fourth dimension to handling following dependent coverage and Medicaid expansion for men with testicular cancer. PLoS 1. 2020;15(9):e0238813. https://doi.org/10.1371/periodical.pone.0238813 PMID: 32936794; PMCID: PMC7494102.

-

Osazuwa-Peters N, Barnes JM, Megwalu U, Adjei Boakye E, Johnston KJ, Gaubatz ME, et al. State Medicaid expansion condition, insurance coverage and phase at diagnosis in caput and neck cancer patients. Oral Oncol. 2020;110:104870. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.oraloncology.2020.104870 Epub 2020 Jul 3. PMID: 32629408.

-

Baugher AR, Finlayson T, Lewis R, Sionean C, Whiteman A, Wejnert C, et al. Health care coverage and Preexposure Prophylaxis (PrEP) use among men who have sex with men living in 22 US cities with vs without Medicaid expansion, 2017. Am J Public Health. 2021;111(four):743–51. https://doi.org/10.2105/AJPH.2020.306035 Epub 2021 Jan 21. PMID: 33476242; PMCID: PMC7958013.

-

Zuvekas SH, McClellan CB, Ali MM, Mutter R. Medicaid expansion and health insurance coverage and handling utilization among individuals with a mental health condition. J Ment Wellness Policy Econ. 2020;23(3):151–82 PMID: 33411677.

-

Olfson M, Wall 1000, Barry CL, Mauro C, Mojtabai R. Bear on of Medicaid expansion on coverage and treatment of depression-income adults with substance use disorders. Health Aff (Millwood). 2018;37(8):1208–15. https://doi.org/10.1377/hlthaff.2018.0124 PMID: 30080455; PMCID: PMC6190698.

-

Fry CE, Sommers BD. Outcome of Medicaid expansion on wellness insurance coverage and access to care among adults with low. Psychiatr Serv. 2018;69(eleven):1146–52. https://doi.org/10.1176/appi.ps.201800181 Epub 2018 Aug 28. PMID: 30152271; PMCID: PMC6395562.

-

McMorrow S, Gates JA, Long SK, Kenney GM. Medicaid expansion increased coverage, improved affordability, and reduced psychological distress for depression-income parents. Health Aff (Millwood). 2017;36(5):808–18. https://doi.org/x.1377/hlthaff.2016.1650 PMID: 28461346.

-

Soni A, Hendryx Chiliad, Simon One thousand. Medicaid expansion under the Affordable Care Deed and insurance coverage in rural and urban areas. J Rural Health. 2017;33(2):217–26. https://doi.org/10.1111/jrh.12234 Epub 2017 Jan 23. PMID: 28114726.

-

Stimpson JP, Kemmick Pintor J, Wilson FA. Clan of Medicaid expansion with health insurance coverage by marital condition and sex. PLoS One. 2019;fourteen(10):e0223556. https://doi.org/10.1371/periodical.pone.0223556 PMID: 31644546; PMCID: PMC6808332.

-

Selden TM, Abdus S, Keenan PS. Insurance coverage of ambulatory care visits in the last six months of 2011-thirteen and 2014, by Medicaid expansion status. 2016 October. In: Statistical brief (medical expenditure panel survey (US)) [net]. Rockville: Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (U.s.a.); 2001. STATISTICAL Cursory #494. PMID: 28422467.

-

Zogg CK, Scott JW, Bhulani Northward, Gluck AR, Curfman GD, Davis KA, et al. Impact of Affordable Care Human action insurance expansion on pre-hospital access to care: changes in adult perforated appendix admission rates after Medicaid expansion and the dependent coverage provision. J Am Coll Surg. 2019;228(ane):29–43.e1. https://doi.org/x.1016/j.jamcollsurg.2018.09.022 Epub 2018 Oct 22. PMID: 30359835.

-

Bloodworth R, Chen J, Mortensen One thousand. Variation of preventive service utilization past state Medicaid coverage, cost-sharing, and Medicaid expansion status. Prev Med. 2018;115:97–103. https://doi.org/x.1016/j.ypmed.2018.08.020 Epub 2018 Aug 23. PMID: 30145344.

-

Gordon SH, Sommers BD, Wilson IB, Trivedi AN. Effects of Medicaid expansion on postpartum coverage and outpatient utilization. Health Aff (Millwood). 2020;39(1):77–84. https://doi.org/ten.1377/hlthaff.2019.00547 PMID: 31905073; PMCID: PMC7926836.

-

Benitez JA, Creel L, Jennings J'A. Kentucky's Medicaid expansion showing early promise on coverage and access to care. Health Aff. 2016;35(3):528–34.

-

Freedman South, Richardson L, Simon KI. Learning from waiver states: coverage effects nether Indiana's HIP Medicaid expansion. Health Aff (Millwood). 2018;37(6):936–43. https://doi.org/10.1377/hlthaff.2017.1596 PMID: 29863935.

-

Huguet N, Hoopes MJ, Angier H, Marino M, Holderness H, DeVoe JE. Medicaid expansion produces Long-term impact on insurance coverage rates in community health centers. J Prim Care Community Wellness. 2017;8(4):206–12. https://doi.org/x.1177/2150131917709403 Epub 2017 May 17. PMID: 28513249; PMCID: PMC5665709.

-

Blumberg LJ, Holahan J. Early on experience with the ACA: coverage gains, pooling of risk, and Medicaid expansion. J Law Med Ethics. 2016;44(4):538–45. https://doi.org/10.1177/1073110516684784 PMID: 28661254.

-

Selden TM, Lipton BJ, Decker SL. Medicaid expansion and marketplace eligibility both increased coverage, with merchandise-offs in admission, affordability. Health Aff (Millwood). 2017;36(12):2069–77. https://doi.org/x.1377/hlthaff.2017.0830 PMID: 29200332.

-

Frean M, Gruber J, Sommers BD. Premium subsidies, the mandate, and Medicaid expansion: coverage effects of the Affordable Care Act. J Wellness Econ. 2017;53:72–86. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jhealeco.2017.02.004 Epub 2017 Mar 6. PMID: 28319791.

-

Courtemanche C, Marton J, Ukert B, Yelowitz A, Zapata D. Early impacts of the Affordable Care Act on health insurance coverage in Medicaid expansion and not-expansion states. J Policy Anal Manage. 2017;36(i):178–210. https://doi.org/x.1002/pam.21961 PMID: 27992151.

-

Decker SL, Lipton BJ, Sommers BD. Medicaid expansion coverage effects grew in 2015 with continued improvements in coverage quality. Health Aff (Millwood). 2017;36(5):819–25. https://doi.org/ten.1377/hlthaff.2016.1462 PMID: 28461347.

-

Sommers BD, Blendon RJ, Orav EJ, Epstein AM. Changes in utilization and health among low-income adults later on Medicaid expansion or expanded individual insurance. JAMA Intern Med. 2016;176(10):1501–nine. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamainternmed.2016.4419 PMID: 27532694.

-

Andersen RM. Revisiting the behavioral model and access to medical care: does it matter? J Health Soc Behav. 1995;36(1):ane–ten.

-

Mulcahy A, Harris K, Finegold K, Kellermann A, Edelman L, Sommers BD. Insurance coverage of emergency intendance for young adults under health reform. N Engl J Med. 2013;368(22):2105–12.

-

Understanding and Using American Community Survey Information. 2019. Retrieved April 12, 2021, from https://world wide web.census.gov/content/dam/Census/library/publications/2019/acs/acs_aian_handbook_2019.pdf

-

Afendulis CC, He Y, Zaslavsky AM, Chernew ME. The impact of Medicare office D on hospitalization rates. Health Serv Res. 2011;46(4):1022–38.

-

Domino ME, Martin BC, Wiley‐Exley E, Richards S, Henson A, Carey TS, et al. Increasing fourth dimension costs and copayments for prescription drugs: an analysis of policy changes in a complex environment. Health Serv Res. 2011;46(3):900–19.

-

Chua KP, Sommers BD. Changes in health and medical spending among young adults under wellness reform. JAMA. 2014;311(23):2437–nine.

-

Sommers BD, Kronick R. The Affordable Intendance Act and insurance coverage for immature adults. JAMA. 2012;307(9):913–4.

-

Akosa Antwi Y, Moriya Every bit, Simon One thousand. Effects of federal policy to insure young adults: evidence from the 2010 Affordable Care Act's dependent-coverage mandate. Am Econ J Econ Pol. 2013;v(iv):1–28.

-

Status of state Medicaid expansion decisions: Interactive map. Retrieved April 21, 2021, from https://www.kff.org/medicaid/issue-brief/status-of-state-medicaid-expansion-decisions-interactive-map/

-

APSE. 2019. Retrieved May 3, 2021, from https://aspe.hhs.gov/

-

Sommers BD, Gunja MZ, Finegold K, Musco T. Changes in cocky-reported insurance coverage, access to care, and health under the Affordable Care Act. JAMA. 2015;314(4):366–74.

-

Griffith K, Evans Fifty, Bor J. The Affordable Care Deed reduced socioeconomic disparities in health care admission. Health Aff (Millwood). 2017;36(eight):1503–10.

-

Karletsos D, Stoecker C. Impact of Medicaid expansion on PrEP utilization in the U.s.a.: 2012–2018. AIDS Behav. 2020:ane–nine.

-

Stoecker C, et al. Association of nonprofit hospitals' charitable activities with unreimbursed Medicaid care after Medicaid expansion. JAMA Netw Open. 2020;3(two):e200012.

Acknowledgements

Non applicative.

Funding

The authors received no financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Author information

Affiliations

Contributions

Yilu Lin did the assay and drafted the manuscript. Alisha Monnette and Lizheng Shi contributed to the critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content. The author(s) read and canonical the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ideals approval and consent to participate

Not applicable. This is a data analysis simply report using de-identified information.

Consent for publication

Not applicative.

Competing interests

The authors declared no conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Boosted information

Publisher'south Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Admission This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution four.0 International License, which permits utilise, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(south) and the source, provide a link to the Artistic Commons licence, and indicate if changes were fabricated. The images or other third party material in this commodity are included in the commodity'southward Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If textile is non included in the commodity'southward Creative Commons licence and your intended apply is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you volition need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The Creative Eatables Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/i.0/) applies to the data made available in this commodity, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

Reprints and Permissions

About this commodity

Cite this article

Lin, Y., Monnette, A. & Shi, L. Furnishings of medicaid expansion on poverty disparities in wellness insurance coverage. Int J Disinterestedness Health 20, 171 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12939-021-01486-3

-

Received:

-

Accepted:

-

Published:

-

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1186/s12939-021-01486-3

Keywords

- Health disinterestedness

- Medicaid expansion

- Poverty disparity

- Insurance coverage

quezadasumpeormses92.blogspot.com

Source: https://equityhealthj.biomedcentral.com/articles/10.1186/s12939-021-01486-3

0 Response to "When Reviewing the Literature on the Effects of Medicaid on Health Care for the Poor"

Enregistrer un commentaire